Ghostbusters

| Ghostbusters | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ivan Reitman |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | Ivan Reitman |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | László Kovács |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25–30 million |

| Box office | $371 million |

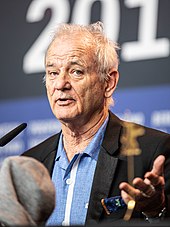

Ghostbusters is a 1984 American supernatural comedy film directed by Ivan Reitman and written by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis. It stars Bill Murray, Aykroyd, and Ramis as Peter Venkman, Ray Stantz, and Egon Spengler, three eccentric parapsychologists who start a ghost-catching business in New York City. It also stars Sigourney Weaver and Rick Moranis, and features Annie Potts, Ernie Hudson, and William Atherton in supporting roles.

Based on his fascination with spirituality, Aykroyd conceived Ghostbusters as a project starring himself and John Belushi, in which they would venture through time and space battling supernatural threats. Following Belushi's death in 1982, and with Aykroyd's concept deemed financially impractical, Ramis was hired to help rewrite the script to set it in New York City and make it more realistic. It was the first comedy film to employ expensive special effects, and Columbia Pictures, concerned about its relatively high $25–30 million budget, had little faith in its box office potential. Filming took place from October 1983 to January 1984, in New York City and Los Angeles. Due to competition for special effects studios among various films in development at the time, Richard Edlund used part of the budget to found Boss Film Studios, which employed a combination of practical effects, miniatures, and puppets to deliver the ghoulish visuals.

Ghostbusters was released on June 8, 1984, to critical acclaim and became a cultural phenomenon. It was praised for its blend of comedy, action, and horror, and Murray's performance was often singled out for praise. It earned at least $282 million worldwide during its initial theatrical run and was the second-highest-grossing film of 1984 in the United States and Canada, and the then-highest-grossing comedy ever. It was the number-one film in US theaters for seven consecutive weeks and one of only four films to gross more than $100 million that year. Further theatrical releases have increased the worldwide total gross to around $371 million, making it one of the most successful comedy films of the 1980s. In 2015, the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. Its theme song, "Ghostbusters" by Ray Parker Jr., was also a number-one hit.

With its effect on popular culture, and a dedicated fan following, the success of Ghostbusters launched a multi-billion dollar multimedia franchise. This included the popular animated television series The Real Ghostbusters (1986), its follow-up Extreme Ghostbusters (1997), video games, board games, comic books, clothing, music, and haunted attractions. Ghostbusters was followed in 1989 by Ghostbusters II, which fared less well financially and critically, and attempts to develop a second sequel paused in 2014 following Ramis's death. After a 2016 reboot received mixed reviews and underperformed financially, a second sequel to the 1984 film, Ghostbusters: Afterlife (2021), was released, followed by Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire (2024).

Plot

[edit]After Columbia University parapsychology professors Peter Venkman, Ray Stantz, and Egon Spengler experience their first encounter with a ghost at the New York Public Library, the university dean dismisses the credibility of their paranormal-focused research and fires them. The trio responds by establishing "Ghostbusters", a paranormal investigation and elimination service operating out of a disused firehouse. They develop high-tech nuclear-powered equipment to capture and contain ghosts, although business is initially slow.

Following a paranormal encounter in her apartment, cellist Dana Barrett visits the Ghostbusters. She recounts witnessing a demonic dog-like creature in her refrigerator utter a single word: "Zuul". Ray and Egon research Zuul and details of Dana's building while Peter inspects her apartment and unsuccessfully attempts to seduce her. The Ghostbusters are hired to remove a gluttonous ghost from the Sedgewick Hotel. Having failed to properly test their equipment, Egon warns the group that crossing the energy streams of their proton pack weapons could cause a catastrophic explosion. They capture the ghost and deposit it in an ecto-containment unit under the firehouse. Supernatural activity rapidly increases across the city and the Ghostbusters become famous; they hire a fourth member, Winston Zeddemore, to cope with the growing demand.

Suspicious of the Ghostbusters, Environmental Protection Agency inspector Walter Peck asks to evaluate their equipment, but Peter rebuffs him. Egon warns that the containment unit is nearing capacity and supernatural energy is surging across the city. Peter meets with Dana and informs her Zuul was a demigod worshipped as a servant to "Gozer the Gozerian", a shapeshifting god of destruction. Upon returning home, she is possessed by Zuul; a similar entity possesses her neighbor, Louis Tully. Peter arrives and finds the possessed Dana/Zuul claiming to be "the Gatekeeper". Louis is brought to Egon by police officers and claims he is "Vinz Clortho, the Keymaster". The Ghostbusters agree they must keep the pair separated.

Peck returns with law enforcement and city workers to have the Ghostbusters arrested and their containment unit deactivated, causing an explosion that releases the captured ghosts. Louis/Vinz escapes in the confusion and makes his way to the apartment building to join Dana/Zuul. In jail, Ray and Egon reveal that Ivo Shandor, leader of a Gozer-worshipping cult in the early 20th century, designed Dana's building to function as an antenna to attract and concentrate spiritual energy to summon Gozer and bring about the apocalypse. Faced with supernatural chaos across the city, the Ghostbusters convince the mayor to release them.

The Ghostbusters travel to a hidden temple located on top of the building as Dana/Zuul and Louis/Vinz open the gate between dimensions and transform into demonic dogs. Gozer appears as a woman and attacks the Ghostbusters, then disappears when they attempt to retaliate. Her disembodied voice demands the Ghostbusters "choose the form of the destructor". Ray inadvertently recalls a beloved corporate mascot from his childhood, and Gozer reappears as a gigantic Stay Puft Marshmallow Man that begins destroying the city. Against his earlier advice, Egon instructs the team to cross their proton energy streams at the dimensional gate. The resulting explosion destroys Gozer's avatar, banishing it back to its dimension, and closes the gateway. The Ghostbusters rescue Dana and Louis from the wreckage and are welcomed on the street as heroes.

Cast

[edit]

- Bill Murray as Peter Venkman

- Dan Aykroyd as Ray Stantz

- Sigourney Weaver as Dana Barrett

- Harold Ramis as Egon Spengler

- Rick Moranis as Louis Tully

- Annie Potts as Janine Melnitz

- William Atherton as Walter Peck

- Ernie Hudson as Winston Zeddemore

In addition to the main cast, Ghostbusters features David Margulies as Lenny Clotch, Mayor of New York, Michael Ensign as the Sedgewick Hotel manager, and Slavitza Jovan as Gozer (voiced by Paddi Edwards). It also features astrologist Ruth Hale Oliver as the Library Ghost,[3] Alice Drummond as the Librarian,[4] Jennifer Runyon and Steven Tash as Peter's psychological test subjects,[5][6] Timothy Carhart as a violinist,[6] and Reginald VelJohnson as a corrections officer.[7] Playboy Playmate Kymberly Herrin appears as a seductive ghost in Ray's dreams.[3]

Roger Grimsby, Larry King, Joe Franklin, and Casey Kasem make cameo appearances as themselves; Kasem in a voice-only role. In addition, Kasem's wife, Jean, appears as the tall guest at Louis' party; along with Debbie Gibson and porn star Ron Jeremy.[5] Director Ivan Reitman provided the voice to Slimer and other miscellaneous ghost voices.[7]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Ghostbusters was inspired by Dan Aykroyd's fascination with and belief in the paranormal,[1][8] which he inherited from his father, who later wrote the book A History of Ghosts;[9] his mother, who claimed to have seen ghosts; his grandfather, who experimented with radios to contact the dead; and his great-grandfather, a renowned spiritualist. In 1981, Aykroyd read an article on quantum physics and parapsychology in The Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, which gave him the idea of trapping ghosts. He was also drawn to the idea of modernizing the comedic ghost films of the mid-20th century by comics such as Abbott and Costello (Hold That Ghost, 1941), Bob Hope (The Ghost Breakers, 1940) and the Bowery Boys (Ghost Chasers, 1951).[8][10]

Aykroyd wrote the script, intending to star alongside Eddie Murphy and his close friend and fellow Saturday Night Live (SNL) alumnus John Belushi, before Belushi's accidental death in March 1982.[1][8] Aykroyd recalled writing one of Belushi's lines when producer and talent agent Bernie Brillstein called to inform him of Belushi's death.[8] He turned to another former SNL castmate, Bill Murray, who agreed to join without an explicit agreement, which is how he often worked.[8] Aykroyd pitched his concept to Brillstein as three men who chase ghosts and included a sketch of the Marshmallow Man character he had imagined. He likened the Ghostbusters to pest-control workers, saying that "calling a Ghostbuster was just like getting rats removed".[10] Aykroyd believed Ivan Reitman was the logical choice to direct, based on his successes with films such as Animal House (1978) and Stripes (1981).[8] Reitman was aware of the film's outline while Belushi was still a prospective cast member; this version took place in the future with many groups of intergalactic ghostbusters, and felt it "would have cost something like $200 million to make".[10][b] Aykroyd's original 70- to 80-page script treatment was more serious in tone and intended to be scary.[8][10]

Reitman met with Aykroyd at Art's Delicatessen in Studio City, Los Angeles, and explained that his concept would be impossible to make. He suggested that setting it entirely on Earth would make the extraordinary elements funnier, and that focusing on realism from the beginning would make the Marshmallow Man more believable by the end. He also wanted to portray the Ghostbusters' origins before starting their business: "This was beginning of the 1980s—everyone was going into business".[8][10] After the meeting, they met Harold Ramis at Burbank Studios. Reitman had worked with Ramis on previous films and believed he could better execute the tone he intended for the script than Aykroyd.[10] He also felt Ramis should play a Ghostbuster. After reading the script, Ramis joined the project immediately.[8]

Although the script required considerable changes, Reitman pitched the film to Columbia Pictures executive Frank Price in March 1983. Price found the concept funny, but was unsure of the project, as comedies were seen to have limited profitability. He said the film would take a big budget due to its special effects and popular cast.[8][10] Reitman reportedly said they could work with $25–30 million;[c] varying figures have been cited. Price agreed, as long as the film could be released by June 1984.[8][9] Reitman later admitted he made up the figure, basing it on three times the budget for Stripes, which seemed "reasonable".[8] This left 13 months to complete the film, with no finished script, effects studio, or filming start date.[9] Reitman hired his previous collaborators Joe Medjuck and Michael C. Gross as associate producers.[11] Columbia's CEO Fay Vincent sent his lawyer Dick Gallop to Los Angeles to convince Price not to pursue the film, but Price disagreed. Gallop returned to the head office to report that Price was "out of control".[8][10]

As the title "Ghostbusters" was legally restricted by the 1970s children's show The Ghost Busters, owned by Universal Studios, several alternative titles were considered, including "Ghoststoppers", "Ghostbreakers", and "Ghostsmashers".[8][12][13] Price parted ways with Columbia early in Ghostbusters' production and became head of Universal Pictures, at which point he sold Columbia the title for $500,000 plus 1% of the film's profits. Given Hollywood's accounting practices—a method used by studios to artificially inflate a film's production costs to limit royalty or tax payouts—the film technically never made a profit for Universal to be owed a payment.[10][12][14]

Writing

[edit]Aykroyd, Ramis, and Reitman began reworking the script, first at Reitman's office, then sequestering themselves and their families on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts. Aykroyd had a home there, and they worked day and night in his basement for about two weeks.[9] Aykroyd was willing to rework his script; he considered himself a "kitchen sink" writer who created the funny situations and paranormal jargon, while Ramis refined the jokes and dialogue. They wrote separately, then rewrote each other's drafts. Many scenes had to be cut, including an asylum haunted by celebrities, and an illegal ghost-storage facility in a New Jersey gas station.[8] Their initial draft was completed when they left the Vineyard in mid-July 1983, and a third and near-final draft was ready by early August.[8][9][15] When Murray flew to New York after filming The Razor's Edge (1984) to meet Aykroyd and Ramis, he offered little input on the script or his character. Having written for Murray multiple times, Ramis said he knew "how to handle his character's voice".[8]

It was decided early on that Ramis's character would be the brains of the Ghostbusters, Aykroyd's the heart, and Murray's the mouth.[10] Aykroyd drew inspiration from fiction archetypes: "Put Peter Venkman, Raymond Stantz, and Egon Spengler together, and you have the Scarecrow, the Lion, and the Tin Man".[8] His concept called for the Ghostbusters to have a boss and to be directed into situations, but Ramis preferred they be in control "of their own destiny" and make their own choices. This led to the development of more distinct identities for the characters: Peter as the cool, modern salesman; Ray as the honest, enthusiastic technician; and Egon as the factual, stoic intellectual.[11]

Reitman thought the most difficult parts of the writing were determining the story's goal, who the villain was and their goal, why ghosts were manifesting, and how a towering Marshmallow Man would appear. The creature was one of many elaborate supernatural entities in Aykroyd's initial treatment, originally intended to emerge from the East River only 20 minutes into the film. It stood out to Reitman but concerned him because of the relatively realistic tone they were taking. Meanwhile, Reitman searched for a special effects studio, eventually recruiting Richard Edlund in the same two-week span.[9][16]

Cast and characters

[edit]

Murray was considered essential to Ghostbusters' potential success, but he was known for not committing to projects until late. Price agreed to fund Murray's passion project The Razor's Edge, believing if it failed it would lose little money, and hoping the gesture would secure Murray's commitment to Ghostbusters.[8] Michael Keaton, Chevy Chase, Tom Hanks, Robin Williams, Steve Guttenberg, and Richard Pryor were also considered for the role.[1][17][18] Christopher Walken, John Lithgow, Christopher Lloyd, Jeff Goldblum, and Keaton were considered to portray Egon.[18][19] Ramis was inspired by the cover of a journal on abstract architecture for Egon's appearance, featuring a man wearing a three-piece tweed suit and wire-rim glasses, his hair standing straight up. He took the character's first name from a Hungarian refugee with whom he attended school, and the surname from German historian Oswald Spengler.[10] Apart from the three main stars, Medjuck was largely responsible for casting the roles.[20]

Hudson auditioned five times for the role of Winston Zeddemore.[8] According to him, an earlier version of the script gave Winston a larger role as an Air Force demolitions expert with an elaborate backstory. Excited by the part, he agreed to the job for half his usual salary. The night before shooting began, he received a new script with a greatly reduced role; Reitman told him the studio wanted to expand Murray's part.[21] Aykroyd said Winston was the role intended for Eddie Murphy, although Reitman denied this.[3][22] Gregory Hines and Reginald VelJohnson were also considered for the part.[23][24]

Daryl Hannah, Denise Crosby, Julia Roberts, and Kelly LeBrock auditioned for the role of Dana Barrett, but Sigourney Weaver attracted the filmmakers' attention. There was resistance to casting her because of the generally serious roles she had played in Alien (1979) and The Year of Living Dangerously (1982). She revealed her comedic background, developed at the Yale School of Drama, and began walking on all fours and howling like a dog during her audition.[d] It was her suggestion for Dana to become possessed by Zuul; Reitman said this solved problems with the last act by giving the characters personal stakes in the events.[9] Weaver also changed Dana's occupation from a model to a musician, saying that Dana can be somewhat strict, but has a soul because she plays the cello.[8]

John Candy was offered the role of Louis Tully. He told Reitman he did not understand the character and suggested portraying Tully with a German accent and multiple German Shepherds, but the filmmakers felt there were already enough dogs in the film. Candy chose not to pursue the role. Reitman had previously worked with Rick Moranis and sent him the script. He accepted the role an hour later.[9][10][15] Moranis developed many aspects of his character, including making him an accountant, and ad-libbed the lengthy speech at Tully's party.[15] Sandra Bernhard turned down the role of the Ghostbusters' secretary Janine Melnitz, which went to Annie Potts. When she arrived for her first day of filming, Reitman rushed Potts into the current scene. She quickly changed out of her street clothes and borrowed a pair of glasses worn by the set dresser which her character subsequently wore throughout the film.[27][10]

William Atherton was chosen for the role of Walter Peck after he had appeared in the Broadway play Broadway. Peck was described as akin to Margaret Dumont's role as a comedic foil to the Marx Brothers. Atherton said: "It can't be funny, and I don't find [the Ghostbusters] in the least bit charming. I have to be outraged."[28] The role of the Sumerian god Gozer the Gozerian, envisioned as a business-suited architect, was originally intended for Paul Reubens. When he passed on the idea, Yugoslavian actress Slavitza Jovan was cast and the character changed to one inspired by the androgynous looks of Grace Jones and David Bowie.[27][29][30] Paddi Edwards was uncredited as the voice of Gozer, dubbing over Jovan's strong Slavic accent.[1][31] Reitman's wife and their children, Jason and Catherine, filmed a cameo appearance as a family fleeing Dana's building, but the scene was cut because Jason was too scared by the setup to perform a second take.[32]

Filming

[edit]

Principal photography began in New York City on October 28, 1983.[1][8][33] On the first day, Reitman brought Murray to the set, still unsure if he had read the script.[8] Filming in New York lasted for approximately six weeks, finishing just before Christmas.[9] Reitman was conscious they had to complete the New York phase before they encountered inhospitable December weather.[34] At the time, choosing to shoot in New York City was considered risky. In the early 1980s, many saw the city as synonymous with fiscal disaster and violence, and Los Angeles was seen as the center of the entertainment industry. In a 2014 interview, Reitman said he chose New York because "I wanted the film to be ... my New York movie".[8] As Reitman was working with comedians, he encouraged improvisation, adapting multiple takes and keeping the cast creations that worked, but directing them back to the script.[15]

Some guerrilla filmmaking took place, capturing spontaneous scenes at iconic locations around the city, including one shot at Rockefeller Center where the actors were chased off by a real security guard.[8] A scene was shot on Central Park West with extras chanting "Ghostbusters" before the name had been cleared. Medjuck contacted the studio, urging them to secure permission to use the word as the title.[10]

The building at 55 Central Park West served as the home of Weaver's character and the setting of the Ghostbusters' climactic battle with Gozer. The art department added extra floors and embellishments using matte paintings, models, and digital effects to create the focal point of ghostly activity.[7][35][36] During shooting of the final scene at the building, city officials allowed the closure of the adjacent streets during rush hour, affecting traffic across a large swath of the city. Gross commented that, from the top of the building, they could see traffic queuing all the way to Brooklyn. At various points, a police officer drew his gun on a taxi driver who refused orders; in a similar incident, another officer pulled a driver through his limo window. When angry citizens asked Medjuck what was being filmed, he blamed Francis Ford Coppola filming The Cotton Club (1984). Aykroyd encountered science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov, a man he admired, who complained, "You guys are inconveniencing this building, it's just awful; I don't know how they got away with this!"[10] Directly next to 55 Central Park West is the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, which is stepped on by the Marshmallow Man.[36]

Other locations included New York City Hall,[36] the New York Public Library main branch,[1] the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts,[37] Columbus Circle, the Irving Trust Bank on Fifth Avenue,[38] and Tavern on the Green. Firehouse, Hook & Ladder Company 8 in the Tribeca neighborhood was used as the Ghostbusters' headquarters.[1][3][39] Columbia University allowed its Havemeyer Hall to stand in for the fictional Weaver Hall, on the condition the university not be identified by name.[39]

Filming moved to Los Angeles, resuming between Christmas and the New Year.[9] Due to the film's use of practical effects, skilled technicians were needed who resided mainly in the city and soundstages that were non-existent in New York.[34] Despite its setting, most of Ghostbusters was filmed on location in Los Angeles or on sets at Burbank Studios. Location scouts searched for buildings that could replicate the interiors of buildings being filmed in New York.[1][34] Reitman tried using the interior of Hook & Ladder 8, but was unable to take it over long enough because it was an active fire station. Interior firehouse shots were taken instead at the decommissioned Fire House No. 23 in downtown Los Angeles. The building design, while common in New York, was a rarity in Los Angeles. An archival photograph of an active crew in Fire House No. 23 from 1915 was hung in the background of the Ghostbusters' office.[34]

Filming in the main reading room of the New York Public Library was only allowed in the early morning and had to be concluded by 10:00 am.[16] The basement library stacks were represented by the Los Angeles Central Library as Reitman said they were interchangeable.[34] The Millennium Biltmore Hotel stood in for the scenes set at the fictional Sedgewick Hotel.[40] Principal photography concluded at the end of January 1984, after between 55 and 62 days of filming.[9][41]

Post-production

[edit]The short production schedule and looming release date meant Reitman edited the film while it was being shot. There was often only time for a few takes.[9][16] Reitman sometimes found making an effects-laden movie frustrating, as the special effects had to be storyboarded and filmed in advance; there was no option to go back and produce new scenes. As Gross described it: "[Y]ou storyboard in advance, that's like editing in advance. You've got a scene, they're going to approve that scene, and we're going to spend nine months doing that cut. There's no second takes, no outtakes, there's no coverage. You can cut stuff, but you can't add stuff. It made [Reitman] so confined that it really bothered him".[41]

A deleted scene involved a segment at "Fort Detmerring" where Ray has a sexual encounter with a female ghost. The scene was intended to introduce a love interest for Aykroyd. Ramis believed it was extraneous to the fast-moving plot, however, so Reitman used the footage as a dream sequence during the mid-film montage instead.[42] Editor Sheldon Kahn sent Reitman black-and-white reels of sequences during filming. They not only allowed him to make changes, but he considered they also helped him understand how to better pace the film. Kahn completed the first full cut three weeks after filming concluded.[9] The final cut runs for 105 minutes.[1]

Music

[edit]The Ghostbusters score was composed by Elmer Bernstein and performed by the 72-person Hollywood Studio Symphony orchestra at The Village in West Los Angeles, California. It was orchestrated by David Spear and Bernstein's son Peter.[43][44] Elmer Bernstein had previously scored several of Reitman's films and joined the project early on, before all the cast had been signed.[43] Reitman wanted a grounded, realistic score and did not want the music to tell the audience when something was funny.[41] Bernstein used the ondes Martenot (effectively a keyboard equivalent of a theremin) to produce the "eerie" effect. Bernstein had to bring a musician from England to play the instrument because there were so few trained ondists. He also used three Yamaha DX7 synthesizers.[43][44] In a 1985 interview Bernstein described Ghostbusters as the most difficult score he had written, finding it challenging to balance the varying comedic and serious tones. He created an "antic" theme for the Ghostbusters he described as "cute, without being really way out". He found the latter parts of the film easier to score, aiming to make it sound "awesome and mystical".[43]

Early on Reitman and Bernstein discussed the idea that Ghostbusters would feature popular music at specific points to complement Bernstein's original score. This includes "Magic" by Mick Smiley, which plays during the scene when the ghosts are released from the Ghostbusters headquarters. Bernstein's main theme for the Ghostbusters was later replaced by Ray Parker Jr.'s "Ghostbusters".[43][44] Bernstein personally disliked the use of these songs, particularly "Magic", but said, "it's very hard to argue with something like ["Ghostbusters"], when it is up in the top ten on the charts".[43]

Music was required for a montage in the middle of the film, and "I Want a New Drug" by Huey Lewis and the News was used as a temporary placeholder because of its appropriate tempo. Reitman was later introduced to Parker Jr. who developed "Ghostbusters" with a similar riff to match the montage.[10] There were approximately 50 to 60 different theme songs developed for Ghostbusters by different artists before Parker Jr.'s involvement, though none was deemed suitable.[45][46] Huey Lewis was approached to compose the film's theme, but was already committed to work on Back to the Future (1985).[1]

Design

[edit]During the thirteen-month production, all the major special effects studios were working on other films. Those that remained were too small to work on the approximately 630 individual effects shots needed for Ghostbusters. At the same time, special effects cinematographer Richard Edlund planned to leave Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and start his own business. Reitman convinced Columbia to collaborate with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), which also needed an effects studio, to advance Edlund $5 million to establish his own company, Boss Film Studios.[8][9] According to Edlund, lawyers used much of the setup time finalizing the contract, leaving only ten months remaining to build the effects studio, shoot the scenes, and composite the images.[8] The Boss Film Studios' team was split to complete work on Ghostbusters and MGM's science-fiction film 2010: The Year We Make Contact.[1] The $5 million effects came in at $700,000 over budget.[16] The strict filming schedule meant most of the effects shots were captured in one take.[41] Gross oversaw both the creation of Boss Film Studios, and the hiring of many conceptual designers including comic book artists Tanino Liberatore (whose work went unused) and Bernie Wrightson (who helped conceive several ghost designs), and storyboarder Thom Enriquez, whose designs contributed to the "Onion Head ghost".[20]

Creature effects

[edit]

Edlund's previous work on the supernatural horror film Poltergeist (1982) served as a reference for the ghost designs in Ghostbusters. Gross said it was difficult to balance making the ghosts a genuine threat while fitting the film's more comedic tone.[47][48] Special effects artist Steve Johnson sculpted the gluttonous, slimy, green ghost then known as the "Onion Head ghost" on set due to the puppet's unpleasant smell.[13][49] The creature was given the name "Slimer" in the 1986 animated television series The Real Ghostbusters.[1] The Slimer design took six months and cost approximately $300,000. After struggling to complete a design due to executive interference, Johnson took at least three grams of cocaine and completed the final design in one night, based in part on Aykroyd's and Ramis's wish for the creature to homage Belushi.[e] The full-size foam rubber puppet was worn by Mark Wilson and filmed against a black background. Puppeteers manipulated the model's movements with cables.[1][50][51]

Aykroyd tasked his friend, referred to as the Viking, with designing the Marshmallow Man, asking for a combination of the Michelin Man and the Pillsbury Doughboy in a sailor hat.[10] The Marshmallow Man outfit was built and portrayed by actor and special effects artist Bill Bryan, who modeled his walk on Godzilla. There were eighteen foam suits, each costing between $25,000 and $30,000; seventeen of them, worn by stuntman Tommy Cesar, were burned as part of filming.[16][52] Bryan used a separate air supply due to the foam's toxicity. There were three different heads for the suit, built from foam and fiberglass, with different expressions and movements controlled by cable mechanisms. The costume was filmed against scale models to finish the effect. The effects team was able to find only one model of a police car at the correct scale and bought several, modifying them to represent different vehicles. The water from a burst hydrant hit by a remote-controlled car was actually sand as the water did not scale down.[16][53][54] The "marshmallow" raining down on the crowd after it is destroyed was shaving cream. After seeing the intended 150 pounds (68 kg) of shaving cream to be used, Atherton insisted on testing it. The weight knocked a stuntman down, and they ended up using only 75 pounds (34 kg). The cream acted as a skin irritant after hours of filming, giving some of the cast rashes.[10]

Johnson also sculpted the Zombie Cab Driver puppet.[55] It was the only puppet shot on location in New York City. Johnson based it on a reanimated corpse puppet he had made for An American Werewolf in London (1981).[55] Johnson and Wilson collaborated on the Library Ghost, creating a puppet operated by up to 20 cables running through the torso that controlled aspects such as moving the head, arms, and pulling rubber skin away from the torso to transform it from a humanoid into a monstrous ghoul.[56] The original Library Ghost puppet was considered too scary for younger audiences and was repurposed for use in Fright Night (1985).[5] The library catalog scene was accomplished live in three takes, with the crew blowing air through copper pipes to force the cards into the air. These had to be collected and reassembled for each take. Reitman used a multi-camera setup to focus on the librarian and the cards flying around her and a wider overall shot.[9][16] The floating books were hung on strings.[16]

Randy Cook was responsible for creating the quarter-scale stop-motion puppets of Gozer's minions Zuul and Vinz, the Terror Dogs, when in motion. The model was heavy and unwieldy, and it took nearly thirty hours to film it moving across a 30-foot (9.1 m) stage for the scene where it pursues Louis Tully across a street.[56] For the scene where Dana is pinned to her chair by demonic hands before a doorway beaming with light, Reitman said he was influenced by Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). A rubber door was used to allow distortion as if something was trying to come through it, while grips concealed in a trapdoor beneath the chair, burst through it while wearing demonic dog-leg gloves.[16] Made before the advent of computer-generated imagery (CGI), any non-puppet ghosts had to be animated. It took up to three weeks to create one second of footage.[16] For Gozer, Slavitza Jovan wore red contact lenses that caused her a great deal of pain, and she wore a harness to move around the set.[7]

Technology and equipment

[edit]Hardware consultant Stephen Dane was responsible for designing most of the Ghostbusters' iconic equipment, including the "proton packs" used to wrangle ghosts, ghost traps, and their vehicle, the Ectomobile. The equipment had to be designed and built in the six weeks before filming began in September 1983.[33][57] Inspired by a military issue flamethrower, the "proton packs" consisted of a handheld proton stream firing "neutrino wand" connected by a hose to a backpack said to contain a nuclear accelerator.[12][58] Dane said he "went home and got foam pieces and just threw a bunch of stuff together to get the look. It was highly machined, but it had to look off-the-shelf and military surplus".[59]

Following Reitman's tweaks to the design, on-screen models of the "proton packs" were made from a fiberglass shell with an aluminum backplate bolted to a United States Army backpack frame.[58] Each pack weighed approximately 30 pounds (14 kg) with the batteries for lighting installed, and strained the actors' backs during the long shoots.[16][59] Two lighter versions were made; a hollow one with surface details for wide shots, and a foam rubber version for action scenes.[16][58] The fiberglass props were created by special effects supervisor Chuck Gaspar, based on Dane's design. Gaspar used rubber molds to create identical fiberglass shells.[59] The "neutrino wand" had a flashbulb at the tip, giving animators an origin point for the proton streams.[16] Fake walls laced with pyrotechnics were used to practically create the damage of the proton streams.[34] The "Psychokinetic Energy meter" ("PKE meter") prop was built using an Iona SP-1 handheld shoe polisher as a base, to which lights and electronics were affixed.[60] The PKE meter prop was designed and built by John Zabrucky of Modern Props in partnership with an outside fabricator.[61] The technology was designed to not be overly fancy or sleek, emphasizing the characters' scientific backgrounds combined with the homemade nature of their equipment.[34]

The Ectomobile was in the first draft of Aykroyd's script, and he and John Daveikis developed some early concepts for the car. Dane developed fully detailed drawings for the interior and exterior and supervised the transformation of the 1959 Cadillac Miller-Meteor ambulance conversion into the Ectomobile.[62] According to Aykroyd, the actual vehicle was "an ambulance that we converted to a hearse and then converted to an ambulance".[63] Early concepts featured a black car with purple and white strobe lights giving it a supernatural glow, but this idea was scrapped after cinematographer László Kovács noted that dark paint would not film well at night. The concept also had fantastic features such as the ability to dematerialize and travel inter-dimensionally. Two vehicles were purchased, one for the pre-modification scenes.[62] Dane designed its high-tech roof array with objects including a directional antenna, an air-conditioning unit, storage boxes and a radome.[64] Because of its size, the roof rack was shipped to Manhattan on an airplane, while the car was transported to the East Coast by train.[33] Sound designer Richard Beggs created the siren from a recording of a leopard snarl, cut and played backward.[64]

Logo and sets

[edit]

In the script, Aykroyd described the Ghostbusters clothing and vehicle as bearing a no symbol with a ghost trapped in it, crediting the Viking with the original concept.[65][66] The final design fell to Gross, who had volunteered to serve as art director. As the logo would be required for props and sets, it needed to be finalized quickly, and Gross worked with Boss Film artist and creature design consultant Brent Boates who drew the final concept, and R/GA animated the logo for the film's opening. According to Gross, two versions of the logo exist, with one having "ghostbusters" written across the diagonal part of the sign. Gross did not like how it looked and flipped the diagonal bar to read top left to bottom right instead, but they later removed the wording. According to Gross, this is the correct version of the sign that was used throughout Europe. The bottom left to top right version was used in the United States as that was the design of the No symbol there.[65]

Medjuck also hired John DeCuir as production designer.[15] The script did not specify where Gozer would appear, and DeCuir painted the top of Dana's building with large, crystal doors that opened as written in the script.[15] The fictional rooftop of 55 Central Park West was constructed at Stage 12 on the Burbank Studios lot. It was one of the largest constructed sets in film history and was surrounded by a 360-degree cyclorama painting. The lighting used throughout the painting consumed so much power that the rest of the studio had to be shut down, and an additional four generators added, when it was in use.[9][34][67] Small models such as planes were hung on string to animate the backdrop.[9] The set was built three stories off the ground to allow for filming from low angles.[16]

The first three floors and street-front of Dana's building were recreated as sets for filming, including the climactic earthquake scene where hydraulics were used to raise broken parts of the street.[7][68] Broken pieces of pavement and the road were positioned outside the real location to create a seamless transition between the two shots.[34] DeCuir said: "They had one night to dress the street. When people went home early in the evening everything was normal, and when the little old ladies came out to walk their dogs in the morning, the whole street had erupted. Apparently, people complained to the New York Police Department and their switchboard lit up."[69] For the scene where Dana's apartment explodes outwards, Weaver stood on set as the stunt happened.[16] Similarly, the scene of Weaver rotating in the air was performed on set using a body-cast and mechanical arm concealed in the curtains, a trick Reitman learned working with magician Doug Henning.[7]

Release

[edit]Test screening and marketing

[edit]Ghostbusters was screened for test audiences on February 3, 1984, with unfinished effects shots to determine if the comedy worked. Reitman was still concerned audiences would not react well to the Marshmallow Man because of its deviation from the realism of the rest of the film.[15] Reitman recalled that approximately 200 people were recruited off the streets to view the film in a theater on the Burbank lot. It was during the opening library scene Reitman knew the film worked. Audiences reacted with fear, laughs, and applause as the Librarian Ghost transformed into a monster.[15] The fateful Marshmallow scene was met with a similar reaction, and Reitman knew he would not have to perform any re-shoots.[9][15] The screening for fellow industry members fared less well. Price recalled laughing as the rest of the audience sat deadpan; he rationalized an industry audience wants failure. Murray and Aykroyd's agent Michael Ovitz recalled an executive telling him, "Don't worry: we all make mistakes", while Roberto Goizueta, chairman of Columbia's parent, The Coca-Cola Company, said: "Gee, we're going to lose our shirts".[8][70]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In the months before its debut, a teaser trailer focused on the "No ghosts" logo, helping it become recognizable far in advance, and generating interest in the film without mentioning its title or its stars.[1][71] A separate theatrical trailer contained a toll-free telephone number with a message by Murray and Aykroyd waiting for the 1,000 callers per hour it received over a six-week period.[13] They also appeared in a video for ShoWest, a theater-owner convention, to promote the film.[72] Columbia spent approximately $10 million on marketing, including $2.25 million on prints, $1 million on promotional materials, and $7 million on advertising and miscellaneous costs including a $150,000 premiere for a hospital and the hotel costs for the press.[73] Including the budget and marketing costs, it was estimated the film would have to make at least $80 million to turn a profit.[47]

Box office

[edit]The premiere of Ghostbusters took place on June 7, 1984, at the Avco Cinema in Westwood, Los Angeles, before its wide release the following day across 1,339 theaters in the United States (U.S.) and Canada.[1][74] During its opening weekend in the U.S. and Canada, the film earned $13.6 million—an average of $10,040 per theater.[f] It finished as the number one film of the weekend, ahead of premiering horror-comedy Gremlins ($12.5 million), and the adventure film Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom ($12 million), in its third week of release.[74][75] The gross increased to $23.1 million during its first week,[g] becoming the first major success for the studio since Tootsie (1982).[h] The film remained number one for seven consecutive weeks, grossing $146.5 million, before being ousted by Purple Rain in early August.[78][79][80]

Ghostbusters regained the number one spot the following week before spending the next five weeks at number two, behind the action film Red Dawn and then the thriller Tightrope.[81][82][83] Ghostbusters remained among the top-three grossing films for sixteen straight weeks before beginning a gradual decline and falling from the top-ten by late October. It left cinemas in early January 1985, after thirty weeks.[76][84] Ghostbusters had quickly become a hit, surpassing Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom as the top-grossing film of the summer, and earning $229 million,[i] making it the second highest-grossing film of 1984, approximately $5 million behind Eddie Murphy's action-comedy Beverly Hills Cop ($234.8 million) which was released in mid-December.[15][85] Ghostbusters surpassed Animal House as the highest-grossing comedy film ever, until Beverly Hills Cop surpassed it six months later.[9][84][85]

Columbia had negotiated 50% of the box-office revenues or 90% of gross after expenses, depending on whichever was higher. Since the latter was the case, the studio received a 73% share of the box office profit, an estimated $128 million.[73][j] The main cast members each received percentages of the gross profits or net participation.[1] A 1987 report estimated Murray alone had earned between $20–30 million from his share.[86][k] Detailed box office figures are not available for territories outside the U.S. and Canada, but Box Office Mojo estimated it to have grossed $53 million, bringing Ghostbusters' worldwide total to $282.2 million.[74][l] The Hollywood Reporter recorded its international gross at the end of 1999 at $126 million.[87] 1984 saw the release of several films that would later be considered iconic of the era, including: Gremlins, The Karate Kid, The Terminator, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Romancing the Stone, and The NeverEnding Story. It was also the first year in box office history in which four films, including Ghostbusters, grossed over $100 million.[88]

Ghostbusters was re-released in the U.S. and Canada in August 1985, grossing a further $9.4 million over five weeks, raising its theatrical gross to $238.6 million[89][90] and surpassing Beverly Hills Cop as the most successful comedy of the 1980s.[85] By the end of 1999, Ghostbusters had grossed $364.6 million worldwide.[87] A restored and remastered version was released in August 2014, at 700 theaters across the U.S. and Canada to celebrate its 30th anniversary. It grossed an additional $3.5 million, bringing the theatrical total to $242.2 million.[91][92] The film has also received limited rereleases for special events and anniversaries.[93][94] Including all reissues since 2000, the film has grossed an estimated $371 million worldwide.[87] Adjusted for inflation, the North American box office is equivalent to $667.9 million in 2020, making it the thirty-seventh highest-grossing film ever.[95]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

Ghostbusters opened to generally positive reviews.[1][96] Roger Ebert gave it three and a half out of four, citing it as a rare example of successfully combining a special effects-driven blockbuster with "sly" dialogue. Ebert noted the effects existed to serve the actors' performances and not the reverse, saying it is "an exception to the general rule that big special effects can wreck a comedy". He also cited Ghostbusters as a rare mainstream film with many quotable lines.[97] Writing for Newsday, Joseph Gelmis described the Ghostbusters as an adolescent fantasy, comparing their firehouse base to the Batcave with a fireman's pole and an Ectomobile on the ground floor.[98]

Deseret News' Christopher Hicks praised Reitman's improved directing skills, and the crew for avoiding the vulgarity found in their previous films, Caddyshack and Stripes. He felt they reached for more creative humor and genuine thrills instead. He complained about the finale, claiming it lost its sense of fun and was "overblown", but found the film compensated for this since it "has ghosts like you've never seen".[99] Janet Maslin agreed that the apocalyptic finale was out of hand, saying Ghostbusters worked best during the smaller ghost-catching scenes.[100] Dave Kehr wrote that Reitman is adept at improvisational comedy, but lost control of the film as the special effects gradually escalated.[101]

Arthur Knight appreciated the relaxed style of comedy saying while the plot is "primitive", it has "far more style and finesse" than would be expected of the creative team behind Meatballs and Animal House. He singled out editors Sheldon Kahn and David Blewitt for creating a sustained pace of comedy and action.[102] Despite "bathroom humor and tacky sight gags", Peter Travers described Ghostbusters favorably as "irresistible nonsense", comparing it to the supernatural horror film The Exorcist, but with the comedy duo Abbott and Costello starring.[103] Time's Richard Schickel described the special effects as somewhat "tacky" but believed this was a deliberate commentary on other ghost films. Ultimately, he believed praise was due to all involved for "thinking on a grandly comic scale".[104][105] Newsweek's David Ansen enjoyed the film, describing it as a teamwork project where everyone works "toward the same goal of relaxed insanity"; he called it "wonderful summer nonsense".[106] Variety's review described it as a "lavishly produced" film that is only periodically impressive.[107]

Reviewers were consistent in their praise for Murray's performance.[m] Gene Siskel wrote that Murray's comedic sensibilities compensated for the "boring special effects".[108] Variety singled out Murray for his "endearing" physical comedy and ad-libbing.[107] Hicks similarly praised Murray, saying he "has never been better than he is here".[99] Schickel considered Murray's character a "once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to develop fully his patented comic character".[104][105] Gelmis appreciated Murray's dismissal of the serious situations to keep them comedic.[98]

The interactions between Murray, Aykroyd, and Ramis, were also generally well received.[103][108] Schickel praised Aykroyd and Ramis for their "grace" in allowing Murray to outshine them.[104][105] Travers and Gelmis said the three main actors worked well as a collaborative force,[98][103] and Hicks described Murray, Ramis, and Aykroyd as wanting "to be like the Marx Brothers of the 80s".[99] Conversely, Kehr believed the pair were "curiously underutilized", but appreciated Murray's deadpan line readings.[101] The New Yorker's Pauline Kael had problems with the chemistry among the three leads. She praised Murray, but felt other actors did not have much material to contribute to the story; she concluded, "Murray's lines fall on dead air".[109] Maslin believed Murray's talents were in service to a film lacking wit or coherence. She noted that many of the characters had little to do, leaving their stories unresolved as the plot began to give way to servicing the special effects instead. However, she did praise Weaver's performance as an "excellent foil" for Murray.[100] Variety described it as a mistake to cast top comedians but often have them working alone.[107] Siskel enjoyed the characters interacting with each other, but was critical of Hudson's late addition to the plot and his lack of development, believing it made "him appear as only a token box office lure".[108]

Accolades

[edit]Ghostbusters was nominated for two Academy Awards in 1985: Best Original Song for "Ghostbusters" by Ray Parker Jr. (losing to Stevie Wonder's "I Just Called to Say I Love You" from The Woman in Red), and Best Visual Effects for John Bruno, Richard Edlund, Chuck Gaspar and Mark Vargo (losing to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom).[12][110] That year, it was nominated for three Golden Globe Awards: Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy (losing to Romancing the Stone),[111] Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy for Murray (losing to Dudley Moore in Micki & Maude),[112] and Best Original Song for Parker Jr., (losing again to "I Just Called to Say I Love You").[113] "Ghostbusters" went on to win the BAFTA Award for Best Original Song, and Edlund was nominated for Special Visual Effects (losing again to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom).[114] It won Best Fantasy Film at the 12th Saturn Awards.[115]

Post-release

[edit]Aftermath

[edit]

Ray Parker Jr.'s "Ghostbusters" spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1984 and 21 weeks on the charts altogether.[45][116] The song is estimated to have added $20 million to the film's box office.[117] Reitman directed the successful "Ghostbusters" music video that included several celebrity cameos.[1][45][46] Shortly after the film's release, Huey Lewis sued Parker Jr., for plagiarizing his 1983 song "I Want a New Drug".[1][46] The case was settled out of court in 1985.[10][46] Parker Jr. later sued Lewis for breaching a confidentiality agreement about the case.[46] In 1984, the filmmakers were also sued by Harvey Cartoons, the owner of Casper the Friendly Ghost for $50 million and the destruction of all copies of the film. Harvey alleged the Ghostbusters logo was based on their character Fatso. The case was decided in Columbia's favor.[118][119]

Murray left acting for four years following the release of Ghostbusters. He described the success as a phenomenon that would forever be his biggest accomplishment and, compounded by the failure of his personal project The Razor's Edge, he felt "radioactive". Murray avoided central roles in films until the 1988 Christmas comedy film Scrooged,[120][121] which used the tagline that Murray was "back among the ghosts".[66][122] In a 1989 interview, Reitman said he was upset at the "little respect" he felt Ghostbusters received and his work was not taken seriously, believing many dismissed it as just "another action-comedy".[121]

Hudson held mixed feelings about Ghostbusters. He regretted the marginalization of his character from the original script and felt Ghostbusters did not improve his career as he had hoped, or been promised. In a 2014 interview, he said: "I love the character and he's got some great lines, but I felt the guy was just kind of there ... I'm very thankful that fans appreciate the Winston character. But it's always been very frustrating—kind of a love/hate thing, I guess."[21] Atherton said fans would call him "dickless" on the streets into the 1990s, to his ire.[7][27]

Home media

[edit]Ghostbusters was released on VHS in October 1985. Paramount Pictures had scheduled the equally popular Beverly Hills Cop to release the day before Ghostbusters, forcing Columbia to release it a week earlier to avoid direct competition. Priced at $79.95, Ghostbusters was predicted to sell well but be outperformed by Beverly Hills Cop because of its lower $29.95 price.[n] The release was supported by a $1 million advertising campaign. The film was the tenth best-selling VHS during its launch week. Columbia earned approximately $20 million selling the rights to manufacture and distribute the VHS.[123][124][125] A record 410,000 VHS units were ordered (exceeded a few months later by Rambo: First Blood Part II's 425,000 unit order). By February 1986, it was estimated to have sold 400,000 copies and earned $32 million in revenue, making it the third best-selling VHS of 1985, after Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (425,000 units, $12.7 million) and Beverly Hills Cop (1.4 million units sold, $41.9 million).[126][127]

Ghostbusters was released in 1989 on LaserDisc, a format then experiencing a resurgence in popularity. The release offered a one-disc version, and a two-disc special edition version featuring deleted scenes, a split-screen demonstration of the film's effects, the screenplay, and other special features. In a 1999 interview for the DVD release, Reitman admitted he was not involved in the LaserDisc versions and had been embarrassed by the visual changes that "pumped up the light level so much you saw all the matte lines", highlighting flaws in the special effects.[128][129][130] Ghostbusters was also the first full-length film to be released on a USB flash drive when PNY Technologies did so in 2008.[131]

Blu-ray disc editions were released for the film's 25th, 30th, and 35th anniversaries in 2009, 2014 and 2019. They featured remastered 4K resolution video quality, deleted scenes, alternate takes, fan interviews, and commentaries by crew members and actors including Aykroyd, Ramis, Reitman, and Medjuck. The 35th-anniversary version came in a limited edition steel book cover and contained unseen footage including the deleted "Fort Detmerring" scene.[132][133][134] The film was released as part of the 8-disc Ghostbusters: Ultimate Collection Blu-ray and Ultra HD Blu-ray boxset in February 2022, also containing its sequels Ghostbusters II (1989) and Ghostbusters: Afterlife (2021), and the 2016 reboot Ghostbusters: Answer the Call. Presented in a ghost trap-shaped box, the release features a 114-minute preview cut of Ghostbusters including deleted scenes, an edited-for-TV version, recorded auditions for Dana, and a 90-minute documentary, "Ghostbusters: Behind Closed Doors" about the film's production.[26][135] Parker Jr.'s "Ghostbusters" received special edition vinyl record releases, one as a glow in the dark record—the other a white record presented in a marshmallow-scented jacket.[136][137] A remaster of Bernstein's score was also released in June 2019, on compact disc, digital, and vinyl formats. It includes four unreleased tracks, and commentary by Bernstein's son Peter.[138]

Merchandise

[edit]Developing merchandise for a film was still a relatively new practice at the time of Ghostbusters' release, and it was only following the success of Star Wars merchandise that other studios attempted to duplicate the idea.[139] The unexpected success of Ghostbusters meant Columbia did not have a comprehensive merchandising plan in place to fully capitalize on the film at the peak of its popularity.[140] They were able to generate additional revenue, however, by applying the popular "no ghosts" logo to a variety of products.[141] Much of the merchandising success came from licensing the rights to other companies based on the success of the 1986 animated spin-off The Real Ghostbusters.[140] Merchandise based directly on the film did not initially sell well until The Real Ghostbusters, which on its own helped generate up to $200 million in revenue in 1988, the same year the Ghostbusters proton pack was the most popular toy in the United Kingdom.[142][139] A successful Ghostbusters video game was released alongside the film.[143] The film also received two novelizations, Ghostbusters by Larry Milne (released with the film), and Ghostbusters: The Supernatural Spectacular by Richard Mueller (released in 1985).[5] "Making Ghostbusters", an annotated script by Ramis, was released in 1985.[8]

In the years since its release, Ghostbusters merchandise has included: soundtrack albums, action figures, books, Halloween costumes, various Lego and Playmobil sets including the Ectomobile and Firehouse,[144][145] board games,[146][147] slot machines,[148] pinball machines,[149] bobbleheads, statues, prop replicas, neon signs, ice cube trays, Minimates, coin banks,[140] Funko Pop figures,[150] footwear,[151] lunch boxes, and breakfast cereals.[84] A Slimer-inspired limited-edition citrus-flavored Hi-C Ecto Cooler drink first released in 1987, was one of the more popular items, and did not cease production until 2001.[144] The Slimer character became iconic and popular, appearing in video games, toys, cartoons, sequels, toothpaste, and juice boxes.[49] There have also been crossover products including comic books and toys that combine the Ghostbusters with existing properties like Men in Black,[152] Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,[153][144] Transformers,[154] and World Wrestling Entertainment.[155]

Thematic analysis

[edit]Capitalism and private industry

[edit]

As described by academic Christine Alice Corcos, Ghostbusters is "a satire on academia, intellectuals, city government, yuppies, tax professionals, and apathetic New Yorkers".[156] It has also been analyzed as an era-appropriate example of Republican, libertarian, or neo-liberal ideology, in particular, Reagan-era economics popularized by United States President Ronald Reagan.[o] Reaganomics focused on limited government spending and deregulation in favor of a free market provided by the private sector of entrepreneurship, profit motives, and individual initiative.[158][159][160] Analysts point to the premise of a small private business obstructed by an arrogant, incompetent bureaucrat (Walter Peck) from a government agency. Peck's interference compromises the Ghostbusters' ghost containment unit, unleashing spirits upon the city and ushering in Gozer's arrival.[158][159] When Peck arrives to shutter the Ghostbusters, Egon affirms "this is private property".[160] In this sense, it is Peck, not Gozer, who represents the true villain.[159][160] Others note that after losing their university jobs, Aykroyd's character is upset because their public sector funding required little of them. He had worked in the private sector where "they expect results".[160] Reitman considered himself a "conservative-slash-libertarian".[160][161]

The Washington Examiner wrote that the private sector arrives to combat the supernatural activity in New York, for a fee, while the government is incapable of doing anything.[160][162] As Vox notes, the mayor, a government representative, is motivated to release the Ghostbusters after being reminded that their success will save the lives of "millions of registered voters", a cynical view of an official who is motivated by what allows him to retain his position.[158] The mayor's choice is ideological: the privatized free market of the Ghostbusters or the government agency Peck represents.[163] Even the police are forced to take Louis/Vinz to the Ghostbusters because they are incapable of dealing with him.[162] Author Ralph Clare highlights that the Ghostbusters reside in a disused firehouse and drive an old ambulance, each sold off as public services fail.[164] Corcos suggests the Ghostbusters are an example of the American free-thinker, representing vigilantes fighting against government overreach that is worsening the issue.[165]

Clare wrote that Ghostbusters embraces the free market in the aftermath of American financial despair in the 1970s, particularly in New York City that led to films set in a gritty, collapsing, crime-ridden, and failed New York, such as Taxi Driver (1976), The Warriors (1979), and Escape from New York (1981).[166] Ghostbusters was created at the beginning of an economic recovery that Clare described as "pure capitalism", focused on the privatization and deregulation to allow the private sector to supplant the government.[157] The necessity of the mayor outsourcing the ghost problem mirrors the real New York government ceding vast areas of real estate to corporations to stimulate renewal.[167] The use of capitalism can be further seen in how Ray, tasked to empty his mind, is incapable of recalling anything but a consumerist mascot; in another example, Dana's refrigerator, which stores consumerist icons, is where she witnesses Zuul.[168]

Inequality, immigrants, and pollution

[edit]The ghosts in Ghostbusters have been interpreted as analogs for crime, homelessness, pollution, and faltering infrastructure and public services.[165][169] Corcos discussed Ghostbusters's negative take on government and environmental regulation.[170] She wrote that the ghosts represent pollutants, remnants of environmental damage, and a reflection of real-life governments refusing to acknowledge environmental problems that affect humanity.[171] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) explicitly does not believe in the ghosts or "waste" the Ghostbusters are collecting and, in turn, the Ghostbusters do not believe the EPA deserves obedience or compliance because of its ignorance.[172] Even though the Ghostbusters have condensed a widespread problem into a small area, they have constructed a dangerous containment unit in a heavily populated area while possessing the unique knowledge to understand how much danger it poses.[173] However, Peck's rigid adherence to government regulation results in him turning off the unit and creating a more dangerous situation.[174]

Clare identified the ghosts as representative of New York's issues with the homeless and ethnic minorities. The ghosts, which were once human, are not acknowledged as such and are treated as a nuisance that the Ghostbusters transport to less desirable areas, similar to real-world gentrification. The Ghostbusters charge a substantial fee for their services and so generally serve the affluent such as the Sedgewick hotel and Dana Barrett, while poorer Chinese citizens pay for their services in meat.[169][175] In this way, Clare argues, Ghostbusters promotes the regeneration of New York City but ignores the cost to the poor and disenfranchised to achieve it.[176] Author Zoila Clark noted that concept art of an unused Chinatown ghost bore similarities to a stereotypical Chinese immigrant including long, braided hair and a triangular agricultural hat.[175]

Immaturity

[edit]Author Nicole Matthews argued the need to present a film targeted at both adults and children leads to the central characters being infantilized and immature.[177] Critic Vincent Canby said a film's profitability was dependent on addressing children who "can identify with a 40-year-old-man with a mid-life crisis and 40-year-old-men in midlife crises who long to fight pirates with cardboard cutlasses".[178] Ghostbusters presents Venkman's immature comedic sarcasm as a means of disarming situations and furthering the narrative. Author Jim Whalley wrote that this presents a clear tonal shift in the sequel; in Ghostbusters, the characters are hired workers just doing their job, whereas in Ghostbusters II they are noble heroes saving the city. In doing so, Ghostbusters II reimagines Venkman's persona as comedic relief instead of a practical tool.[179] The primarily male audience also results in female characters that are either absent or not important to the overall story.[180] Author Jane Crisp wrote that Dana encountering Zuul in her fridge presents a stereotypical view of women being associated with the home and kitchen.[181]

Legacy

[edit]Ghostbusters is considered one of the first blockbusters and is credited with refining the term to effectively create a new genre that mixed comedy, science fiction, horror, and thrills. Ghostbusters also confirmed the merchandising success of Star Wars (1977) was not a fluke. A successful, recognizable brand could be used to launch spin-offs, helping establish a business model in the film industry that has since become the status quo. Once Ghostbusters' popularity was clear, the studio aggressively cultivated its profile, translating it into merchandising and other media such as television, extending its profitable lifetime long after the film had left theaters.[141]

Entertainment industry observers credit Ghostbusters and Saturday Night Live with reversing the negative perception of New York City in the early 1980s.[8][182] Weaver said: "I think it was a love letter to New York and New Yorkers ... the doorman saying, 'Someone brought a cougar to a party'—that's so New York. When we come down covered with marshmallow, and there are these crowds of New Yorkers of all types and descriptions cheering for us ... it was one of the most moving things I can remember".[69][71] It is similarly credited with helping diminish the divide between television and film actors. Talent agent Michael Ovitz said that before Ghostbusters, television actors were only considered for minor roles in film.[8][182] Describing Ghostbusters' enduring popularity, Reitman said "kids are all worried about death and... ghost-like things. By watching Ghostbusters, there's a sense that you can control this, that you can mitigate it somehow and it doesn't have to be that frightening. It became this movie that parents liked to bring their kids to—they could appreciate it on different levels but still watch it together".[15]

Cultural influence

[edit]Ghostbusters was considered a phenomenon and highly influential.[p] The Ghostbusters' theme song was a hit, and Halloween of 1984 was dominated by children dressed as the titular protagonists.[8][141][184] It had a significant effect on popular culture and is credited with inventing the special-effects driven comedy.[q] Its basic premise of a particular genre mixed with comedy, and a team combating an otherworldly threat has been replicated with varying degrees of success in films like Men in Black (1997), Evolution (2001), The Watch (2012), R.I.P.D. (2013), and Pixels (2015).[66][185][186] In 2015, the United States Library of Congress selected Ghostbusters for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". Reitman responded: "It's an honor to know that a movie that begins with a ghost in a library now has a spot on the shelves of the Library of Congress".[187]

In 1984, the Ghostbusters phenomenon was referred to across dozens of advertisements for everything from airlines to dentistry and real estate. The "-busters" suffix became a common term used at both local and national stages, being applied to topics like the United States national budget ("budgetbusters"), agriculture ("cropbusters"), B-52s ("nukebusters"), sanitation ("litterbusters"), or Pan American Airlines ("pricebusters"). Similarly, the "no ghosts" logo was modified to protest political candidates like Ronald Reagan and Walter Mondale to Mickey Mouse by striking Disney workers.[188] Other contributions to the cultural lexicon included "Who ya gonna call?" from Parker Jr's "Ghostbusters",[46] and Murray's adlib of "this chick is toast" against Gozer to imply she was finished or doomed over the scripted line of "I'm gonna turn this guy into toast". This is thought to be the first historic usage of "toast" as a slang term.[189]

Ghostbusters quickly developed a dedicated fan following that has continued to thrive in the years since.[144] Despite its mainstream success, it is considered an example of a cult blockbuster—a popular film with a dedicated fanbase.[63][190][191] It is popular globally, inspiring fan clubs, fan-made films,[192] art,[193] and conventions.[194] Fans dressed as Ghostbusters occasionally burst into the main reading room of the New York Public Library.[8] The 2016 crowdfunded documentary Ghostheads follows various fans of the series and details the effect it has had on their lives, interspersed with interviews from crew, including Aykroyd, Reitman, and Weaver.[195][196] A separate 2020 documentary, Cleanin' Up the Town: Remembering Ghostbusters, details the film production.[197] Memorabilia from the film is popular, with a screen-used proton pack selling for $169,000 at a 2012 auction.[198] In 2017, a newly discovered ankylosaur fossil was named Zuul crurivastator after Gozer's minion.[199][200]

Ghostbusters was turned into a special-effects laden stage show at Universal Studios Florida, which ran from 1990 to 1996, based mainly on the final battle with Gozer. The 2019 Halloween Horror Nights event at Universal Studios Hollywood and Universal Studios Florida hosted a haunted maze attraction featuring locations, characters, and ghosts from the film.[201][183] The film has also been homaged or explicitly referred to across a variety of media including film,[r] television,[205] and video games.[206][207] Aykroyd reprised his Ghostbuster character for a cameo in Casper (1995),[202] and the celebratory parade at the film's denouement inspired the ending of the 2012 superhero film The Avengers, showing the world celebrating the eponymous team's victory.[208]

Critical reassessment

[edit]Ghostbusters's positive reception has lasted well beyond its release, and it is considered one of the most important comedy films ever made.[144][209] It is listed in the 2013 film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[210] On its 30th anniversary in 2014, The Hollywood Reporter's entertainment industry-voted ranking named it the seventy-seventh best film of all time.[211] That year, Time Out rated Ghostbusters five out of five, describing it as a "cavalcade of pure joy".[212] Empire's reader-voted list of the 100 Greatest Movies placed the film as number 68.[213] In 2014, Rolling Stone readers voted Ghostbusters the ninth-greatest film of the 1980s.[214] Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes offers a 95% approval rating from 79 critics, with an average rating of 8.1/10. The site's consensus reads: "An infectiously fun blend of special effects and comedy, with Bill Murray's hilarious deadpan performance leading a cast of great comic turns".[215] The film also has a score of 71 out of 100 on Metacritic based on eight critical reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[216]

In 2001, the American Film Institute ranked Ghostbusters number 28 on its 100 Years...100 Laughs list recognizing the best comedy films.[217] In 2009, National Review ranked Ghostbusters number 10 on its list of the 25 Best Conservative Movies of the Last 25 Years, noting the "regulation-happy" Environmental Protection Agency is portrayed as the villain and it is the private sector that saves the day.[218] In November 2015, the screenplay was listed number 14 on the Writers Guild of America's 101 Funniest Screenplays.[219] In 2017, the BBC polled 253 critics (118 female, 135 male) from across 52 countries on the funniest film made. Ghostbusters came ninety-fifth.[220]

Ghostbusters is considered one of the best films of the 1980s, appearing on several lists based on this metric, including: number two by Film.com,[221] number five by Time Out,[222] number six by ShortList,[223] number 15 by Complex,[224] number 31 by Empire,[225] and it appears on Filmsite's non-ranked list.[226] It also appeared on several media outlets' best comedy film lists—ranked number one by Entertainment Weekly,[227] number four by IGN,[228] number 10 by Empire,[229] number 25 by The Daily Telegraph,[230] and number 45 by Rotten Tomatoes,[231] which also listed the film number 71 on its list of 200 essential movies to watch.[232] Others have named it one of the best science-fiction films,[233] best science-fiction comedies,[234] and best summer blockbusters.[84][235] Murray's Peter Venkman appeared at number 44 on Empire's 2006 list of its "100 Greatest Movie Characters".[236]

Sequels and adaptations

[edit]

The film's success spawned the Ghostbusters franchise, comprising animated television shows, film sequels, and reboot.[237] Ghostbusters was followed by the 1986 animated television series The Real Ghostbusters. It ran for 140 episodes over seven seasons across six years, and itself spawned a spin-off Slimer-centric sub-series, comic books, and merchandise. It was followed by a sequel series, 1997's Extreme Ghostbusters.[237][238] A film sequel, Ghostbusters II, was released in 1989. Despite breaking box office records and attracting an estimated two million more people to its opening than Ghostbusters, the sequel earned less than the original and received a less enthusiastic response.[239][240] Even so, the popularity of the actors and characters led to discussion of a third film.[240] The concept failed to progress for many years because Murray was reluctant to participate. In a 2009 interview, he said:

We did [Ghostbusters II] and it was sort of rather unsatisfying for me, because the first one to me was ... the real thing. And the sequel ... They’d written a whole different movie than the one [initially discussed] ... so there's never been an interest in a third Ghostbusters, because the second one was disappointing ... for me, anyway.[241]

Aykroyd pursued a sequel through to the early 2010s.[240] Ghostbusters: The Video Game was released in 2009, featuring narrative contributions from Ramis and Aykroyd, and voice acting by Murray, Aykroyd, Ramis, Hudson, Potts, and Atherton. Set two years after Ghostbusters II, the story follows the Ghostbusters training a recruit (the player) to combat a ghostly threat related to Gozer. The game was well-received, earning award nominations for its storytelling. Aykroyd has referred to the game as being "essentially the third movie".[240][242] Ghostbusters: The Return (2004) was the first in a planned series of sequel novels before the publisher went out of business. Several Ghostbusters comic books have continued the original group's adventures across the globe and other dimensions.[144][243]

Following Ramis's death in 2014, Reitman determined the creative control shared by himself, Ramis, Aykroyd, and Murray was holding the franchise back and negotiated a deal to sell the rights to Columbia; he spent two weeks convincing Murray. Reitman refused to detail the deal but said "the creators would be enriched for the rest of our lives, and for the rest of our children's lives". He and Aykroyd founded Ghost Corps, a production company dedicated to expanding the franchise, starting with the 2016 female-led reboot Ghostbusters (later retitled Ghostbusters: Answer the Call).[s] Before its release, the reboot was beset by controversies. After its release, it was considered a box-office bomb with mixed reviews.[t] The franchise returned to the original two films with the sequels, Ghostbusters: Afterlife (2021), directed by Reitman's son Jason, and Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire (2024).[252][253]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Columbia-Delphi Productions and Dan Aykroyd's Black Rhino are credited as the production companies behind Ghostbusters.[1][2]

- ^ The estimated $200 million required to realize Dan Aykroyd's original vision for Ghostbusters is equivalent to $612 million in 2023.

- ^ The 1984 budget of $25–30 million is equivalent to $76.5 million–$91.8 million in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[9][10][25][26]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[8][10][49][50]

- ^ The opening weekend gross of $13.6 million is equivalent to $39.9 million in 2023.

- ^ The opening week gross of $23.1 million is equivalent to $67.7 million in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[1][70][76][77]

- ^ The United States and Canada theatrical gross of $229 million is equivalent to $672 million in 2023.

- ^ The estimated $128 million profit is equivalent to $375 million in 2023.

- ^ The estimated $20–$30 million earned by Bill Murray is equivalent to $58.7 million–$88 million in 2023.

- ^ The 1984 worldwide box office gross of $282.2 million is equivalent to $828 million in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[99][104][105][108][109]

- ^ The $79.95 and $29.95 cost of a VHS cassette in 1985 is equivalent to $227.00 and $85.00, respectively, in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[157][158][159][160]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[8][71][141][183]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[8][71][141][183]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[46][202][203][204]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[244][245][246][247]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[248][249][250][251]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Ghostbusters (1984)". American Film Institute Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Freeman, Hadley (October 27, 2011). "My favourite film: Ghostbusters". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Castrodale, Jelisa (June 6, 2014). "30 Things You Need to Know About Ghostbusters on Its 30th Anniversary". People. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Ghostbusters librarian actress Alice Drummond dies aged 88". BBC News Online. December 5, 2016. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Kiang, Jessica (June 8, 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About Ghostbusters". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2019.